Be honest. How many times have you bought options that expired worthless?

If you’re dabbling in the options market, I’m willing to bet you’ve picked more losers than winners. Without a defined strategy and a willingness to adapt, the options market is an excellent device for transferring money from the proletariat to the proficient.

Selling Options To Collect Premium

Every investor knows the idiom, “the options market is a zero-sum game,” but what does that mean? In simple terms, every trade has two sides; excluding transaction costs, one side’s gain is the other side’s loss.

When we buy options, we pay a premium to a counterparty that assumes a certain amount of risk on our behalf.

Conversely, when we sell options, we collect a premium for taking on a certain amount of risk.

A Simplified Zero-Sum Options Example

Billy Buyer thinks a particular stock will go down, and Stan the Man is selling options for that stock.

- When Billy purchases a put option, Stan is obligated to buy 100 shares of the underlying stock if Billy decides to exercise the contract.

- If Billy is right and the stock price falls below the option’s strike price, Stan could be on the hook for significant losses, and Billy will likely collect a tidy sum.

- If Billy is wrong and the stock price “moves against him,” Stan keeps the premium, and the option expires worthless.

Billy paid a premium for the privilege—but not the obligation—to sell shares to Stan for a predetermined price. This is risky for Stan, so he collects the premium to assume that risk.

I’m not going to tell you to stop buying options; there’s a time and place for every trade. What I am going to do is educate you on selling options to collect premiums without losing your shit.

Selling Options Obstacle #1: The Lingo

First, we must understand that financial markets are opaque, and the terminology is dense. Reading about option strategies can often feel like consuming a word salad designed to confuse rather than inform:

Long, delta, strangle, short, call, straddle, put, strike, gamma, max pain—ugh! Just put me out of my misery.

It’s a lot to remember, but if you start with a few basics and small trades, you’ll survive long enough to memorize the terminology.

Rethink How You Understand Calls & Puts

If you’ve never sold a contract to open a trade, it’s often easy to think about options from a buyer’s perspective—i.e., calls mean we believe the stock will go up and puts that the stock will go down.

But when selling options, the opposite holds true: if we sell a call, we don’t want the stock to go up, and if we sell a put, we don’t want it to go down.

Since this can get confusing faster than you can say “undefined risk,” take my advice and start thinking about every trade from both sides. No matter if we’re dealing with a call or a put, there is always an “option writer” (the party selling the option) and an “option buyer” (self-explanatory).

For every party that wants an option to expire in the money, there’s a counterparty that does not.

Most Options Held To Expiration Expire Worthless

This is a misleading data point, so let’s dig into it before we continue.

If you search for “how many options expire worthless,” you’ll be greeted by a hundred carbon copies of the same blog post warning you, dear investor, that the conventional wisdom is wrong. It’s like an urban legend at this point, and it goes like this:

A common claim is that 90% of options expire worthless, and that therefore it is better to be a seller of options than a buyer of options. This claim misstates a statistic published by the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), which is that only 10% of option contracts are exercised. But just because only 10% are exercised does not mean the other 90% expire worthless.

StockOptionsChannel along with about a thousand other blogs, too.

Unfortunately, these blogs mention the same shitty statistic from the Chicago Board Options Exchange, and they all fail to link to a source showing the CBOE data.

However, I did find a similar statistic that suits our needs: the Options Clearing Corporation says that only 6% of all options are exercised. According to the debunkers, naive traders extrapolate from that data to assume that option writers are winning the trade 94% of the time.

It’s An Options Market

Just like stocks on stock exchanges, options are traded on option exchanges.

The premium for any given option contract fluctuates due to changes in the underlying stock price and other market forces. An option we buy today might be worth twice as much tomorrow. Maybe it expires next month, but we can sell it early for a profit if there’s enough liquidity, and most option buyers do so.

Only six percent of all options are exercised, but the OCC also mentions that more than 72% of all option contracts are closed in the market before expiration (same source linked above). That leaves only 22% expiring without value.

If only 22% expire worthless, does that mean buyers have the advantage? Not exactly. An option closed early doesn’t indicate that it was profitable. Furthermore, a single option expiring worthless might be part of a more complex, profitable position.

You need to understand that although many options expire worthless, and many more are closed before expiration, these numbers don’t reveal the bigger picture.

So, if we plan on selling options, how do we decide which ones will go down in value after they are sold?

Implied Volatility & Pricing Options

Understanding implied volatility is crucial whether we are buying or selling options. Implied volatility is an educated guestimate of how volatile the market thinks a particular stock will be in the future. It’s one of several parameters of the Black-Scholes model (a fancy formula for calculating premiums).

Implied volatility is a measure of the expected movement in the underlying stock. Higher implied volatility implies a greater likelihood of a movement in the stock price.

Outsized price movements are inherently risky; therefore, the premiums for options with high IV will be more expensive to compensate an option writer for the additional risk.

The thing is, although implied volatility indicates how volatile traders expect the price of a stock to be in the future, there are a few things to keep in mind:

- it’s only an estimate, and the real stock price movement could be significantly higher or lower;

- it doesn’t tell us anything about which direction the stock will move; and

- it doesn’t even tell us the stock will move in a direction—a stock oscillating between 5% up and 5% down rapidly produces the same high IV as a large directional move.

IV Crush

Here’s a fun tidbit (unless it happens to you): option buyers can correctly guess the directional movement of a stock and still lose money due to a phenomenon known as IV crush.

Earnings reports, product launches, clinical trials, and other significant events can send the price of a stock flying or crash it into the dirt. This elevated level of uncertainty increases implied volatility because the market expects a larger-than-normal move in the stock price.

When implied volatility goes up, option premiums follow.

After the news is released, the stock price might move significantly, but the implied volatility collapses.

The unknown is now known, the stock price settles into its new position, the implied volatility returns to normal levels, and options premiums come careening back to earth.

Although the premium might adjust in the buyer’s favor due to favorable stock price movement, the outsized effect of removing implied volatility from the calculation can sometimes negate the gains.

This is a blog post about selling options, but here’s a quick tip for buying them: if the IV is higher than historical averages, think twice—especially if there’s a looming catalyst on the calendar.

Making Money Even When We’re Wrong

IV crush is one of an option writer’s best friends. There has been more than one occasion where I’ve sold an option and been wrong about the direction, only to be saved by IV crush and still made money.

But that’s not a strategy; that’s luck. We cannot simply sell the options with the highest IV and hope for an IV crush to save our skin. Sometimes the price moves violently against us, and the IV remains high (or goes higher!) because the market doesn’t know what will happen next.

The point of this section is to re-iterate how vital implied volatility is to option premiums. Greater IV equates to more uncertainty which equates to more risk which equates to more premium.

Option Strategies With Undefined Risk

Before we finally talk about how to sell options without blowing up our account, we need to cover “undefined risk.” I think the best way to illustrate undefined risk would be to jump into an example.

Totally Made Up Company ($FAKE) stock is currently trading at $50 per share. Last week it was trading at $75, but news of a scandal involving the CEO of $FAKE caused it to drop by roughly 33%.

Stan the Man has done his due diligence on Totally Made Up Company and determined that their financials are hot garbage. The IV is elevated because of the recent price action, and the premiums for call options are looking juicy.

Short interest is in the double digits, meaning short sellers hold extensive positions against $FAKE. Stan decides that $FAKE’s days are numbered, and there’s no way the stock will return to previous highs.

He decides to write five call options expiring in one month at a strike price of $60 per share. Due to the high IV, the premium for this option is $4 per share, so Stan pockets $2,000 of premium and hopes that $FAKE stays flat or moves lower between now and the expiration date.

The buyer of these options has the right, but not the obligation, to execute and force Stan to sell 500 shares for $60 per share. Stan doesn’t own any shares of $FAKE, so if the buyer takes this action, he’ll have to go to the market and buy 500 shares to sell to the option holder.

Since $FAKE is currently trading at $50, no option buyer will exercise for $60 unless they feel unreasonably charitable.

Easy money, right? (Queue the ominous music swelling in the background)

Blowing Up Your Account Selling Naked Calls

$FAKE is a fickle mistress, and the market knows it. Stan has assumed considerable “undefined risk” for a quick buck. If he’s lucky, $FAKE will do what he wants, and Stan walks away with $2k.

If he’s unlucky, the CEO resigns, the company makes a bullish product announcement that wasn’t “priced in,” and $FAKE moves back up to $75 per share. Then this happens:

- The option holder exercises the five contracts.

- Stan doesn’t own any shares of $FAKE, so he spends $37,500 to acquire 500 shares.

- The option holder pays Stan the strike price of $60 per share for a total of $30,000 and takes his 500 shares.

- Stan got paid $2,000 in premium but lost $7,500 by buying high and selling low for a grand total of $5,500 in losses.

That’s a big hit, but it’s not the end of the world. If Stan is really, really unlucky, $FAKE is elevated to meme status, and a bunch of folks on r/wallstreetbets decide that Stonks Only Go Up, the short sellers get squeezed, and the stock flies to $400 per share.

If that happens, Stan is looking at roughly $200,000 in losses. Stan is no longer the Man.

Former option trader and statistician Nassim Taleb coined a well-worn metaphor for accepting undefined risk to earn small, incremental rewards: “Picking up pennies in front of a steamroller.”

The amount of money Stan was risking to make $2k is undefined because there is no theoretical limit to how high a stock can be priced in the market.

So how can Stan sell those calls while defining his risk?

Losing Less Money Selling Covered Calls

Going back to the original trade, Stan could have purchased 500 shares of $FAKE at $50 per share for $25,000 and then sold the five options for $2,000. This is a covered call strategy.

- If $FAKE trades sideways, Stan pockets the premium and unloads the shares, making $2k.

- If $FAKE goes back up to $75 per share, Stan keeps the $2k premium and sells the shares at the strike price of $60 per share for $30k, giving him a total profit of $7k.

- If $FAKE flies to $400 per share, nothing changes: he misses out on the short squeeze gains but still pockets $7k, and profit is profit.

- However, there’s one new variable of risk:

- When Stan sold the naked calls, $FAKE could go bankrupt, and Stan would still walk away with $2k in premium.

- In the covered call scenario, if $FAKE goes to $0, Stan would lose his $25k stock investment minus the $2k in premium for a grand total of $23k in losses.

$23k is the maximum amount of money Stan could lose with covered calls in the unlikely scenario that $FAKE goes bankrupt between now and the expiration date.

That’s not nothing, but it’s capped. The risk is defined.

Every investment strategy involves some manner of risk. The key to defining a safe strategy for writing options is to be sure that the stakes are well-known and defined before making the trade.

Closing The Trade Before Expiration

Remember that only six percent of all options are exercised. More often than not, option writers close their positions well before the expiration date.

Say we want to sell a cash-secured put for $FAKE. A cash-secured put is equivalent to the covered call described above, but instead of owning shares to define the risk, we set aside enough cash to buy the shares if the put is exercised. The money secures the position, then we sell the put to collect the premium.

While waiting for the option to expire, let’s say the underlying stock goes on a run and gains 25%. This will likely result in the premium for our option dropping to a tiny number, maybe even pennies per share. We could wait for the option to expire or repurchase it and keep the difference.

In fact, if the premium drops by a significant percentage, there’s rarely a scenario where we would want to wait. The stock price might fall before the expiration date, so wouldn’t it be better to spend a few bucks now to lock in our gains?

Okay, we understand that if the underlying moves in our favor, we should probably repurchase the option early, but what if the underlying doesn’t move at all? Do we hold until expiration?

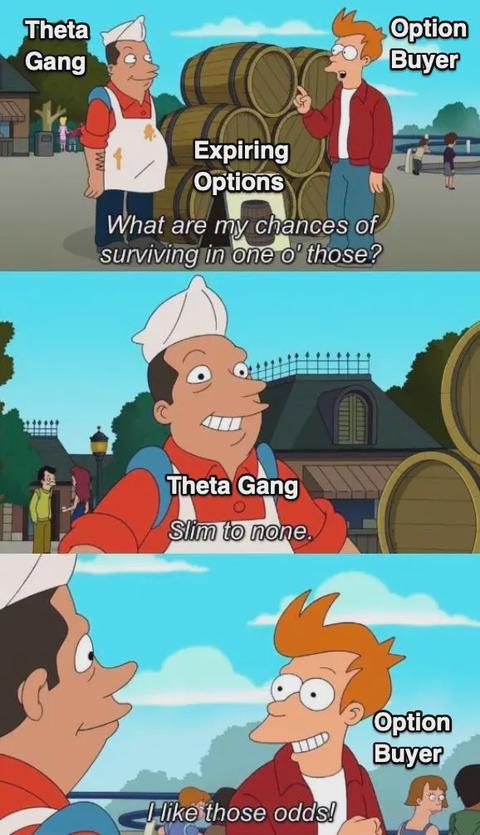

Say Hello To Theta Gang

Surely you have noticed: all things being equal, besides the expiration date, an option expiring next week is much cheaper than an option expiring next month. As time marches toward expiration, the extrinsic value of the option decays to zero (and don’t call me Shirley).

Think of the price of any given stock as a random walk. Since the price is constantly in flux, the probability that an option will finish in the money goes up the further in the future the expiration date.

This is intuitive—more time allows for more chance of random events to occur. Here’s a thought experiment:

I will roll two dice every two seconds for one minute and add the value of each roll cumulatively. You pay me $5 before I begin; if the final total is over 250, I’ll pay you $10.

Let’s make the same bet, still adding up to 250, but I have to roll the dice for two minutes. The payout is still $10, but the likelihood that I roll over 250 is higher, so you’ll need to pay me much more than $5, or I won’t risk it.

(If you’re curious, I’d have to roll roughly seven or less on average to win the first bet, but I would have to roll around four or less on average to win the second bet.)

So, more time equals more risk, which equals more premium.

Theta measures how sensitive the value of an option is to the passage of time. In other words, it measures the decay in extrinsic value as the option approaches expiration.

Theta decay is not linear. An option’s extrinsic value goes to zero at expiration, but as a general rule, it will lose a third of its value during the first half of its life and the remaining two-thirds in the second half.

So, option writers do have an advantage over option buyers. The buyer is purchasing a potentially depreciating asset. In a non-volatile market, the seller only needs to sit back and wait before repurchasing the option at a lower price.

Sell high, buy low, baby. Theta Gang 4 Lyfe.

Selling Options Obstacle #2: Grokking The Greeks

This wouldn’t be an option article without talking about the “Greeks.” If you read the previous section, you’re already familiar with one of the Greeks: Theta.

What Is A Greek?

The Greek values represent how sensitive an option’s price is to changes in the underlying, such as the changing price of the stock.

They’re called “the Greeks” because most of them are denoted by Greek letters, but some of them are just entirely made-up words (I’m looking at you, “zomma”).

Three Greeks Matter Most To Option Writers

The Wikipedia page for the Greeks lists seventeen different values, including obscure measurements like “Color” and “Ultima.” However, to devise strategies for selling options, we’ll primarily focus on three Greeks: Delta, Vega, and Theta.

We’ve talked enough about Theta, so let’s briefly look at Delta and Vega.

Vega: Sensitivity To Volatility

We know that increased volatility increases premiums (for more on volatility, jump back to the section on IV above). Vega is the amount per share that an option’s value will gain as volatility rises by 1 percent.

We pay attention to Vega mostly when writing options for non-volatile stocks—especially if we are trading a short straddle. A short straddle is where you sell a call and a put with the same expiration and strike price. This is a classic premium harvesting strategy for sleepy stocks that don’t move much.

To calculate the straddle’s Vega, we must add the Vega of both options. A straddle is particularly sensitive to volatility because an increase in volatility causes the price of both options to increase.

Delta: The Easiest Greek To Understand

Delta is a number between 0.0 and 1.0 for calls or 0.0 and -1.0 for puts. (It’s pretty common to drop the leading zero and negative sign when referring to the Delta of an option, so if you see someone refer to a put with 32 Delta, they mean -0.32)

Delta is simple: it measures how much an option’s price will change if the underlying stock price moves by one dollar. The cost of a call option with 25 Delta will increase by 25 cents if the underlying stock goes up by $1.

High Delta means an option is particularly sensitive to movements in the underlying stock.

Delta As A Proxy For Probability

One of the coolest things about Delta is that we can use it for a rough approximation of the probability that an option will expire in the money. The math isn’t identical, but Delta is close enough to the percent moneyness of an option that everyone uses it as such when eyeballing the book.

So, a put option with a Delta of 16 has a roughly 84% chance of expiring worthless. One part of a good selling strategy is identifying high-premium, low-delta options.

How To Decide Which Options To Sell

We need to compose a plan that fits our risk appetite and involves the kinds of stocks we’re familiar with. This will be different for everyone, but most strategies have some commonalities.

- Liquidity. We plan to close before expiration most of the time. Therefore, we ensure the options have plenty of liquidity. If there’s no Volume on a day-to-day basis for a particular option, we can’t repurchase the option because there’s no market. If there’s limited liquidity, the spread between the bid and the ask will be wide, eating into our profits.

- Position Size. Rather than putting all of our money into a single trade, we diversify our risk. I aim for no more than 5% of my capital tied up in any given ticker. I may write many small options for twenty different companies. These combine into a decent return while avoiding single-ticker black swan events from wiping out my account.

- Familiarity. We have our thumb on the pulse of a particular company or sector—or at the very least, we know which sectors to avoid due to having zero knowledge about those stocks. I don’t bother writing options for biotech or pharma stocks because I don’t know enough about their products, and they are prone to massive drops.

After selecting stocks and options that fit the above criteria—and before writing a single option—remember the broad strokes we’ve covered today:

- Define your risk. All the planning in the world won’t prevent a single trade with undefined risk from ending the adventure early.

- Manage Implied Volatility. Be cognizant of the IV, especially if it’s higher than usual levels. (Editor’s Note: From personal experience, selling puts on high IV is how you get stuck buying GameStop shares at $32 on 21 October 2022).

- Let Theta Go To Work. Selling options is “boring money,” but in the immortal words of D’Angelo Barksdale, money be green. Sit back and allow Theta to turn an option into worthless paper.

That’s it for today. I’ve given you general information, explainers, and rules-of-thumb rather than step-by-step strategies because it’s essential to understand these core concepts to sell options without losing your shit.

We might do a series of more specific strategies in the future, but for further reading, check out Investopedia, or perhaps have a look at a popular writing strategy called The Wheel.